The second my eyes pop open at some god-awful farmer hour, my hand reflexively grabs the lota (shiny little brass water pot), standing all tall and proud on my nightstand. I hitch up my saree between my legs and out I stumble into pre-dawn darkness, nearly clotheslining myself on the neighbor’s cow, while humming some regional tune so off-key it could qualify as assault.

My quest is a secluded spot. Somewhere, the newspaper boy or milkman won’t catch me mid-squat. Maybe behind those bushes? Or that vacant corner near the well?

That’s what people think happens every morning in India, right? We tumble out of bed, pick our favorite street corner, do the deed, and spend the rest of the day dodging yesterday’s droppings.

Except, guess who has a perfectly functional bathroom some twenty feet from her bed? Complete with commode, running water, and a jet spray that would make your fancy bidet weep?

This girl. And literally everyone else she knows.

The Mishras, two houses away, keep lavender-scented candles in theirs. The aunty next door has a little plant.

But sure, why let boring reality ruin age-old stereotypes where every Indian rides an elephant to work and treats the entire subcontinent like one giant open-air toilet?

Agreed, the toilet crisis was real through the ’90s and early 2000s when the country was still grappling with poverty and the aftermath of economic struggles. But that was old India.

Since 2014, India has built over 100 million toilets, transforming entire towns.

Yet, scroll through any social media, and you’ll still find “SHOCKING Indian Street Food” videos with comments from people who’ve sworn off visiting India based on a fifteen-second clip.

Meanwhile, London had open sewers flowing through the streets until the mid-1800s. New York battled cholera outbreaks from poor sanitation well into the 1900s. Paris? Don’t even get me started on what people threw out their windows. And nobody’s making viral TikToks about French hygiene or British plumbing because those issues don’t define them any longer.

Then why does South Asia’s old stigma refuse to die, long after the dirt’s been washed away?

So, let’s park the elephants for a second and see what life actually looks like in the cleanest city of a nation, somehow still famous for being filthy.

Welcome to India’s cleanest city, Indore.

And nope! We didn’t just wake up one morning, grab a mop, and self-proclaim ourselves the cleanest. Indore has earned the title, one dustbin, one spotless street, and one determined citizen at a time.

Smacked in the middle of the country, Indore is that neat little pinprick on the map most travelers speed past between Mumbai’s chaos and Delhi’s drama. It doesn’t have snow-capped peaks or postcard beaches. What it does have is heart and history.

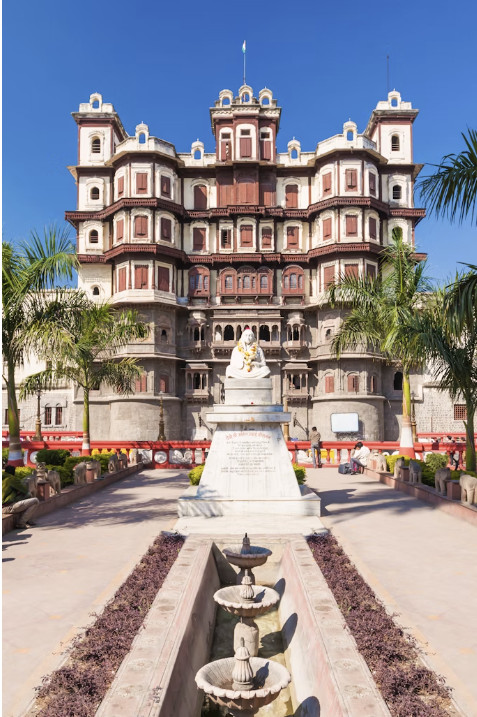

Indore is tucked against the Vindhyanchal ranges, home to Rajwada, Lalbagh Palaces, and other Holkar-era landmarks, it once thrived under the rule of the legendary Queen Ahilyabai Holkar. The city’s roots extend back to the Gupta period, when it was called Indrapura, named after the Indreshwar Mahadev Temple.

So what does living in Indore actually feel like?

Most mornings start around 6:15 AM, and the first creature to greet me is Bhura, the street dog and undisputed mayor of our lane. You’ll find plenty of his kind across Indore, snoozing under parked cars, sprawled on car roofs, guarding closed shops, and napping in spots that make you scratch your head, wondering how they even got there.

Bhura’s an orange-brown mutt with a torn ear, a limp that comes and goes with his mood, and a swagger that says, “This lane’s mine, and I’m the king here”. He’s got a lady love somewhere down the corner and seven puppies from that scandalous affair. All of whom treat the lane like ancestral property.

He minds his business, mostly, unless you’re Reena aunty, the street sweeper, who somehow manages to summon all his wrath by simply setting foot in the lane.

Their feud kicked off one brutal summer morning when she tried to settle the dust and accidentally drenched Bhura and his favorite coat mid-nap.

Traumatized, the orange-brown tyrant declared war. He’d prowl the lane, snatch her broom, dart off with her chappal, or just bark whenever he feels like asserting dominance.

Reena Aunty, naturally, fights back by waving sticks, soaking his favorite coat, hiding his puppies, or unleashing a string of profanities that could make the gods cover their ears.

Their morning tug-of-war is so ritualistic, it doubles as my backup alarm. On the rare days mine fails, their chaos kicks in, and by the time they’ve called a truce, I’m already out on my thirty-minute writer’s walk.

Outside, the colony’s just beginning to yawn awake. Colonel Sharma, my retired-army neighbor two houses down, is already in position, perched on his porch in a white banyan and a checked lungi, sipping chai like it’s part of a drill. His son, a future army man in the making, is doing push-ups and squats under his father’s silent but severe supervision.

They both look up as I pass.

“Good morning,” I greet.

The Colonel nods, eyes narrowing in silent critique of my slightly pouchy belly. I can almost hear his thoughts: Day one in boot camp, and this human penguin would be crying in the corner.

I ignore the look, like I’ve done for most of my adult life, and turn the corner.

The poha-jalebi vendor is already unlocking his cart, performing his morning rituals. First, he folds his hands to the tiny framed god hanging from the cart roof, lights an incense, and waves it around the stove. Then he pours a bit of chai on the street, an offering to whoever’s listening, or maybe for Bhura, who’s usually lurking nearby, feigning nonchalance.

By then, the regulars start trickling in. Half-awake men in chappals, women in cotton nighties, schoolkids with open ties and poha in hand. The smell hits first, that holy mix of mustard seeds, curry leaves, lemon, and nostalgia, followed by the sizzle of jalebis dunked in syrup.

I pass by without grabbing my share. (Don’t worry, I’ll pick some up on my way back.)

Indoris (residents of Indore) are what we lovingly call chatoras (passionate snackers). The kind who wake up at six, splash water on their faces, and shovel through plates of poha before touching the morning newspaper. It’s not unusual for an Indori to drive twenty or thirty minutes across town just for that one shop that makes that one chaat just right.

The straight road ahead takes me to a temple. The bhajans (prayers) echo through the soft morning air. A flock of pigeons scatter as a scooter zooms past. The city’s waking up now with the ominous sound of shutters rattling open, the clang of milk cans, and someone calling out for fresh coriander.

A vegetable vendor slips off his cart. Within seconds, fifteen people rush to help. Someone lifts the cart, another picks up the fallen brinjals, and someone else cracks a joke to ease his embarrassment.

No one’s ever in a hurry here. Indore moves at its own pace, where everyone steals time for kindness.

By the time I head back home, the city’s fully awake. Rickshaws honk lazily, someone’s hanging laundry on a balcony, and the scent of frying onions floats through the air. I shower, grab a quick bite, and step out again, this time to meet Indore in daylight.

The Heart of the Old City

At Rajwada, the heart of the old city, Indore, time folds differently. The palace stands tall, grand, slightly weary, like a grandmother in heavy jewelry who’s seen too much but still dresses up every morning. Around it, the market hums with life.

A boy’s flying a kite dangerously close to the temple spire. A woman’s bargaining like her life depends on that last fifty-rupee discount. A chaiwala (tea man) tells me, completely unprovoked, that his daughter just topped her class.

My destination is Khajuri Bazaar, the old book market, where the narrowest lanes twist and turn. Each one is jam-packed with stacks of second-hand books piled precariously high. I’ve spent days, no, weeks, wandering these galis during my student life, nose deep in musty pages that once cost me a week’s pocket money but opened the whole universe of literature.

At my favorite stall, the shopkeeper, Karim Bhai, greets me with a grin.

“Ah, Komal! Still chasing stories instead of working on yours?” He teases and pats the cooler before flicking it on and opens a small, hidden shelf of exclusive titles reserved for regulars like me.

As I flip through a dog-eared novel, he leans on the counter, spilling the latest bazaar gossip: whose son just settled abroad, which daughter is getting married, and who had a minor tiff with the neighbor last week.

We chuckle over old tales, I nod at a stack of classics he’s set aside for me, and by the time I step back into the sun, it’s afternoon. I wander aimlessly now, notebook tucked under my arm, collecting glances, overhearing jokes, and snippets of life too small for headlines but big enough to hold in memory.

Evening in Indore arrives like a sigh of relief.

I was to meet Neha at 56 Dukaan, my best friend for over a decade, and the only person who’s seen me ugly-cry over burnt paratha.

She’s already there when I arrive, waving from a bench she’s claimed in the chaos. Around us, the air crackles with frying oil and chatter of office workers, college kids, and entire families.

We find our rhythm quickly, plates balanced on our laps.

“Remember our first time here?” Neha asks, grinning.

“You mean when you spilled dahi bada all over my lap?”

“And you still wanted to hang out with me after.”

“Maybe I was hungry for more than just food,” I retort.

She laughs, the kind that makes her whole face crinkle up. We fall into comfortable silence.

Around us, people come and go, vendors call out orders, someone’s kid drops a jalebi and gets handed another one immediately.

What strikes me, sitting here, is how the paper plates land in bins, not on the ground. How the sweeper moving through the crowd gets a nod, not ignored. Small things that would’ve been impossible ten years ago.

Then night descends, and Sarafa Bazaar wakes up. The jewelry shops shed their gold for ghee, streets shimmer under fairy lights, and the scent of jalebi mingles with laughter. Everyone’s a food critic and a poet after 10 PM. Strangers share benches and anecdotes. Friends share plates and sorrows.

I stand there, poha in one hand, malpua in the other, watching the world glisten. Neha’s already three jalebis deep and showing no signs of stopping.

When we finally walk home, the streets are quieter. Bhura’s back on guard duty, curled up near my gate, tail twitching in a dream.

How We Got Here

In 2014, Prime Minister Modi launched the Swachh Bharat Mission, intending to make Indian cities clean. Indore was ranked 149th out of 476 cities that year. By 2016, we’d clawed up to 25th and all the way to number one by 2017. We’ve been there ever since.

So what happened? Did we discover some secret formula? Hire consultants? Pray harder?

Nope. We figured out a system where everyone contributed their bit.

Streets get swept often overnight, so you wake up to clean roads instead of yesterday’s trash. Waste collection vehicles arrive on schedule, playing a specific tune attributed to the city’s achievement to get your attention, with proper sections for your household waste that YOU gotta keep sorted in respective bins.

And yes, we’re billed monthly for the service. Garbage bins that actually make sense, blue for dry waste, green for wet, are placed every hundred meters. And people ACTUALLY use them!

Our Safai mitras have proper tools, uniforms, and training to keep public spaces clean, including public toilets that you can find every 300 meters.

But the real shift is how Indoris stopped treating cleanliness like the government’s problem and started treating it like personal responsibility. Shopkeepers sweep the pavement in front of their stores like it’s written into their lease. If you get caught littering, the fines hurt enough to make you think twice before tossing that wrapper.

What’s Gone

The old, dirty Indore is gone. Gone is the trash, the litter scattered on every corner, the plastic bags dancing in the wind like nobody’s problem. Some parks are gone too, paved over for flyovers and development that the city needed, but my childhood didn’t ask for.

Gone is that granny who lived around the corner, the one who’d sit on her porch every evening and hand out Melody chocolates to passing kids. We’d race our bikes past her house just for those chocolates. We lost her to coronavirus. Nobody sits on that porch anymore.

The banyan tree where I’d spend hours, swallowing Ruskin Bond, Premchand, JK Rowling, George RR Martin, has been replaced by this magic-less four-story glass complex.

Gone is the little Komal who used to peddle around these streets on her pink bicycle with her two chhotis (braids) flying behind her, donning those chiffon skirts that had no business being on a bike.

And gone with her is her childish imagination, innocence, and naivety.

If you asked this writer what she’s lost, the list would be never-ending.

But if you’d prod her about her earnings? She’d flash her Happydent-white smile and tell you that she’s earned the million-dollar peace that settles in her bones, memories that can wake her up from her grave. Mornings that smell like fresh air instead of rot. Streets where kids can play without stepping over garbage. A city that decided it deserved better and actually became it. Friends who show up when her scooter dies. Family dinners that don’t get interrupted by power cuts. The quiet pride of living somewhere that proved everyone wrong and still doing it.

What It Feels Like to Leave

When I travel to other Indian cities, Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, places people have actually heard of, I notice things I never used to notice.

Overflowing bins on street corners. Plastic bags caught in trees like depressing urban decorations. That general acceptance of mess as inevitable. Just part of the package of living in India.

And every single time, I think: but it’s not inevitable. We proved it’s not.

Those cities have things Indore will probably never have. Better job opportunities, bigger career prospects, and more of everything that supposedly matters when you’re trying to build a life.

But they, too, have a long way to come and understand that it’s the bare minimum to actually breathe without your lungs filing a formal complaint, walk in the street without having to play the hop game and that it’s totally normal for strangers to stop and help you push your dead scooter to the nearest pump while simultaneously riding their own bike with one leg.

I miss Indore when I’m gone. And not in some poetic, sobbing way. Instead, it’s this dull ache that sits in my chest, reminding me that somewhere, Reena aunty is sweeping our lane at 7 AM, and the poha-jalebi vendor knows exactly how I like mine, and the neighbor’s aunty is probably watering my plants without being asked.

If You Actually Want to Visit Indore

Come between October and March when the weather is pleasant and isn’t actively trying to murder you. Summers here hit 45°C.

And if you happen to stumble here during Rangpanchami (the Holy cousin of Holi)? Brace yourself for colored water, flying powder, chaos that would make Holi look organized, and a city that will somehow clean itself spotless by sunrise. It’s worth witnessing once, preferably while wearing clothes you don’t care about.

For Landmarks: we’ve got the Rajwada Palace (Indore’s Postcard), Lal Bagh Palace (where folks of the Holkar dynasty really lived), the Khajuri Bazaar (for book lovers), and Khajrana Ganesha Temple.

For food, and let’s be honest, this is why you’re really here, go hungry and stay late in Sarafa Bazaar (The midnight food heaven), Chappan Dukaan, or you can have your Poha-jalebi at literally every decent corner of the streets.

If your soul needs spirituality along with street food, you can visit Mahakaleshwar Jyotrilinga in Ujjain to the north (on the banks of Kshipra) and Omkareshwar Joytrilinga to the south (along the Narmada). Both are short drives away.

For quick escapes at the outskirts, we’ve got Ralamandal Wildlife Sanctuary (19 km away), Patalpani Falls (35 km southwest), Mandu and Jam Gate (For breath-taking Vindhyanchal Ranges views), Tincha Falls, Lotus Lake, and Maheshwar ghats.

How to get here: Devi Ahilyabai Holkar Airport connects to major cities. Indore Junction trains go everywhere. National highways link to Mumbai, Delhi, and everything in between.

Where to stay: From Marriott, Sayaji, to shared spaces, Indore offers accommodation in every budget range.

Pro tip: Bring comfortable walking shoes and an appetite that doesn’t quit. Don’t be surprised when strangers start chatting about your entire life story within five minutes. That’s just how we are. Also, segregate your waste properly—green for wet, blue for dry—or the locals will judge you quite verbally.

What This Means

Cleanliness isn’t really about garbage trucks and color-coded bins, though those help. It’s about decency. Respecting the place you live and the people you share it with. Not leaving your mess for someone else because that someone else is Reena, and she deserves better.

Indore isn’t special because we’re richer, or better educated, or blessed with genius governance. We’re special because enough people decided to care.

That’s it. The whole secret everyone keeps asking about. Just regular people who got tired of being told Indian cities can’t be clean or organized.

This morning, I watched Reena sweep the lane while Bhura watched from a distance, probably plotting his next slipper heist. She hummed while she worked. Some old Hindi film song that I’ve heard her humming a thousand times.

And I thought: maybe that’s what home actually is. Not the things that stay the same forever, because nothing does, but the rhythms that keep going even when everything else changes.

The trees are gone. The mess is gone. That chaotic, unpredictable version of childhood is gone. But the people who care enough to keep sweeping? They’re still here.

Someone just needed to start first. The rest of us followed.

If you liked this story, feel free to check out some of my other articles!

1 comment

Its like you read my mind You appear to know so much about this like you wrote the book in it or something I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a little bit but instead of that this is excellent blog A fantastic read Ill certainly be back