What Is the Baby Milk Scam in Nepal?

There are a number of common scams to which desperate beggars sometimes use to survive, but the baby milk scam I encountered in Nepal and India is one that has always enraged me like no other.

I’d never have believed that one day, I’d actually break bread with someone who partakes in the baby milk scam. Sometimes life has a funny way of upturning our assumptions and biases, leaving us with more questions than clarity.

How the Baby Milk Scam Works

For the baby milk scam, a beggar sits outside a convenience store with a baby that’s often not even their own. They approach foreign passerby and, in a sorrowful tone, explain that their baby needs milk, but they have no money to buy it.

“No money, just milk”, the beggar insists every time. And apparently, the baby needs a particularly expensive imported milk – which the store conveniently stocks. As soon as the passerby is out of sight after purchasing, the milk is returned to the store in exchange for cash.

Why the Baby Milk Scam in Nepal Feels So Different From Other Scams

Don’t get me wrong, I understand that some people genuinely don’t have opportunities and must resort to begging. I almost always give to beggars, and with eye contact and a smile – even just a few coins, in acknowledgment of our shared humanity.

But, the baby milk scam really rubs me the wrong way.

Binta was a ‘baby milk lady’. I saw her every day on my way to school whilst studying in Nepal, and I absolutely despised the disingenuity of that scam and its exploitation of babies and unwitting travelers.

An Unexpected Connection With a “Baby Milk Lady”

One day when I was out of town, I found out–much to my disbelief–that my boyfriend at the time had actually made friends with her. He had donated his old blankets to her when he was about to leave town for the summer. It was a noble move, and she really took to him. I, on the other hand, was baffled, given that he and I felt the same repudiation for the baby milk scam – but I also admired his compassion and ability to separate ‘Binta’ as a human in need, from ‘Binta, the scammer’..

When a Kathmandu Beggar Invited Us Into Her Home

When he and I returned to town, Binta invited us over for food and chai. That’s how we found ourselves following her deep into a slum constructed of shoddy shacks of tarp, bamboo, and sheet metal.

As we walked, neighbors waved to us and shook our hands. Kids darted through the alleys, their playful cries piercing the air and merging with the sound of chickens clucking. We passed by rudimentary, improvised housing units with dirt floors, smoke from open fires for cooking drifting out of entryways. Aside from the obvious poverty of the surroundings, it felt like visiting any tight-knit, off-the-beaten-path locality.

The slum, we learned, was populated by gypsies from Rajasthan, India. They had traveled to Kathmandu some time ago in search of work and better living conditions.

The language barrier meant that I might have missed or misinterpreted some details, but what I took from it is that they were actual gypsies by ancestry. As a wandering Jew with a soft spot for fellow wanderers, I thought that was pretty cool.

Once inside Binta’s shack, she carefully prepared homemade spiced chai tea with milk and some aloo paratha (flatbread with potatoes and spices inside) as we chatted with her and her husband.

We talked about their kids, our studies in Nepal, life in Kathmandu, and other everyday topics, just like we would with any other new friends. The language barrier necessitated rather basic conversation, but it felt like we were truly connecting on a very human level.

Despite the strange normality of this encounter, I was still waiting for the other shoe to drop: surely this visit was actually about asking us for money, right? But to my surprise, no request for cash ever came. We just ate, drank, chatted, and went home.

How One Visit Changed My Perspective on Nepal Scams

The experience completely reframed my view of the baby milk ladies. Ok, so I still didn’t agree with the ethics of this way of making a living–but I understood that the character of people behind it might not be as inherently exploitative as I had projected.

Binta was just a woman who happened to have a job I despised. But lots of people have jobs I personally would consider unethical. Founders whose policies harm the environment and their workers while padding the pockets of a few. Salespeople peddling products that don’t do what they promise. Factory farm owners.

In the grand scheme of things, I reasoned, Binta’s lifestyle wasn’t even as unethical as these things – and she and her tribe faced systemic obstacles and clearly didn’t have many options in life, which made me feel guilty for having judged her.

When I left town, I also donated my blankets to her, and walked away with a sense of empathy that I’d not felt before. I realized that I’d been collapsing the baby milk ladies into the narrow category of ‘unethical scammers’, but now they were three dimensional for me.

If this story ended here, it would be just a feel-good tale with an ending that ties up loose ends and is easy to stomach. That would be nice, wouldn’t it? However, the story doesn’t end here.

Returning to Nepal and Seeing Binta Again

I saw Binta again 9 years later when I visited Nepal in 2022.

I had just entered my old neighborhood, and less than five minutes later, a voice called out to me. “Hey! I remember you! How are you?”

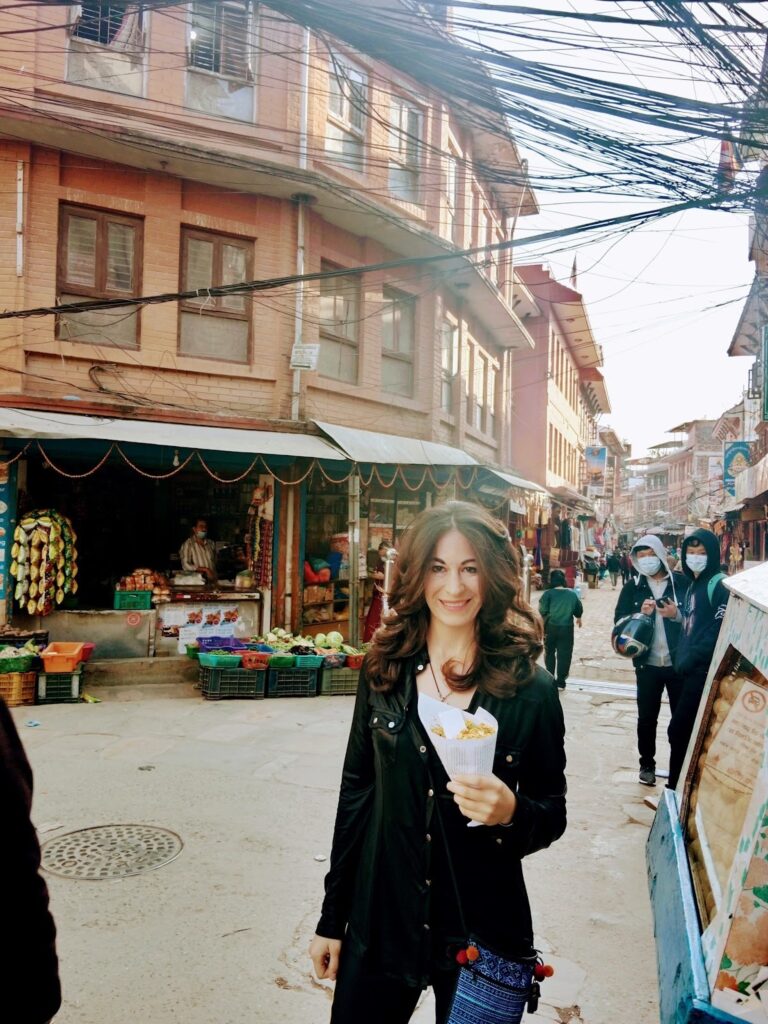

There she was, this time selling some coinpurses on the corner outside of my favorite fresh produce shop. She quickly refreshed my memory, recalling my ex-boyfriend, the blankets, and our meal together.

“You’ve got to come visit us again!” she effused, in between telling me about her new coinpurse business. I felt so proud of her and touched that she’d moved on from the baby milk scam. People actually need coinpurses, and these ones were cute!

This time, my defenses were down. I knew from past experience that a friendly visit to Binta’s neighborhood didn’t need to be about money – it could just be a token of friendship. And, I couldn’t believe that she remembered me. She meets new people all the time, and we hadn’t seen each other in 9 years!

A few days later, I found myself traipsing the familiar path down to the slum. Binta gave me the updated tour, proudly pointing out that she now lived in a concrete dwelling which offered much better protection from the elements. I felt so so touched at her determination to move up in the world despite innumerable obstacles that come with being a poor immigrant in Nepal.

As soon as we got settled inside, however, the tone changed. It became one that I interpreted as performative poverty.

For most of the visit, Binta spoke mournfully about how hard life was and about the difficult circumstances that she and her friends and family faced.

At first, I felt nothing but compassion. Life is clearly extremely hard for these folks. They were born into conditions that they didn’t choose, and they try their best anyway.

In between verbal validation of the difficulties, I sometimes tried to share bits of my own life. After all, if Binta and I were friends, shouldn’t we both be able to share and be heard?

However, I noticed that my attempts to share seemed to fall on deaf ears. The only topics that resulted in ongoing conversation were about the village’s hardships. Part of this was surely due to language – they probably couldn’t understand some of what I said – but part of it felt like a firm lack of interest in me as a person. Others were present too, but one even asked me any questions about my own life.

At this point, I felt the strangest cocktail of emotions: Guilt over my misplaced expectation that people who clearly have a hard time in life should meet me on the level of genuine friendship. Binta and I are not equals – I have much more power as a result of my privilege; had it been a silly fantasy to imagine that our friendship could truly bridge that gap?

I also felt indignance that my visit had been framed as one of genuine friendship, only to turn into what felt like a performance. The poverty was real, yet felt exaggerated in somberness of tone and in the fact that there didn’t seem to be room for much else in the conversation.

9 years ago, I’d felt like I was visiting Binta as a peer. This time, I felt like I was visiting as an onlooker being force-fed a guilt-inducing poverty tour, without discourse at any other level entertained.

While I understand fully that some people do face an extreme amount of genuine hardship, I also saw the lives of this group as more three-dimensional than that. They had children, played games, and had close communal ties. Poverty was a part of their lives, but surely it wasn’t the whole thing.

There were so many other things we could have talked about alongside their difficulties, but it felt like the display of hardship was the main purpose of the visit. As though they were purposefully reducing their existence to one of suffering, curated for my viewing.

I started to get the feeling that they were going to end the visit by asking me for money. I mentally prepared myself for it, deciding internally that I could offer 1000 rupees. After a few more minutes of hearing about their difficulties, I mentally rose that amount to 2,000 rupees. Then 2,500.

A New Version of the Baby Milk Scam in Nepal?

Exactly as predicted, the other shoe dropped: Binta explained that winter was coming, and that she and her family and neighbors desperately needed warm blankets. She had a particular store in mind located right down the road, where I could buy some blankets for around the equivalent of $200 USD.

I don’t remember how many blankets she requested, but I do remember trying not to drop my jaw at the enormity and assumptiveness of the ask. I also wondered whether this arrangement was similar to the baby milk scam: Perhaps they already had blankets, and would simply resell them, allowing the shopkeeper and herself to make money from my guilt and sense of obligation.

Fire rose in my belly. I felt insulted and degraded by the idea that I might just be cast as the naive foreigner who will either fall for anything, or be guilted into something unwillingly.

However, I reasoned, it was also entirely possible that this was a genuine ask borne of palpable need, and that maybe it was uncomfortable for Binta, too. It’s not easy to ask people for support. Perhaps she felt she had no other choice and needed to construct this scenario in order to try to meet her and her family’s very real bodily needs.

How awful would it be if I were just projecting a discompassionate fantasy of ill intent on these poor, disadvantaged people? But then again, she used to be an actual scammer. My thoughts continued to swirl round in circles, oscillating between suspicion of her motives and guilt over entertaining that thought.

In the end, I offered 4,000 rupees – around $35 at that time. It was far less than her ask. She was clearly disappointed. The hope that had hung in the air fell to the ground. Our friendship, I felt, was conditional upon my willingness and ability to offer a certain amount of support.

“But who am I to judge them?” Said a voice in my head.

“But who are they to invite you home under false pretenses, and try to guilt you into dropping a couple hundred bucks?” Said another voice.

The first voice chimed back in: “They have no way to know that you don’t make much money, or that you live and travel at a budget below that of your peers.”

Ultimately, I walked away feeling guilty, despite the fact that I had offered substantially more than what I was comfortable with. However, I offered to post on a local Facebook group to spread the word about the village’s need for blankets.

A few weeks later, Binta gleefully messaged me a video of a truckload of warm blankets being dropped off. The Facebook post had actually worked, and a couple of wealthy foreign monks had caught wind of the campaign.

To this day, I don’t know whether Binta and her friends resold the blankets, or actually used them. One could argue that even if they were resold, the money was used to meet other real needs, like healthcare, food, or school fees for children. All it takes is a glance into Binta’s slum to understand that real need absolutely exists.

In the coming months and even years, Binta occasionally sent me voice notes and videos, sometimes asking for money. Once she told me that her landlord would kick her out the next morning if she didn’t pay 3 months rent.

I explained, guilt-ridden, that I simply don’t have substantial amounts of money that I can keep sharing without compromising my own needs.

Another time, she sent me a video of various people in her village asking for jackets.

One of the guys in the video was a sweet old man I used to give money to daily…until a friend saw him changing from normal, decent clothes into a raggedy begging outfit. And, I once saw him counting a truly fat stack of 500-rupee notes. He, too, obviously had real need–but was it as much as he was projecting?

This is not a story with a neat, tidy ending. Instead, it ends with uncomfortable questions.

At which point is it immoral to lie or cheat if you’re simply trying to meet your basic needs and don’t have better options?

As travelers with comparatively more privilege, wealth, and opportunity, where does our responsibility begin and end? What are our obligations to each other, as parts of an interconnected human community?

And, perhaps most salient of all – which carries more moral weight in the end: her very real need to survive, even if it means resorting to manipulation, or my hurt at feeling exploited by someone I wanted to trust?

I still don’t know the answers, and that’s ok. Sometimes, not knowing means that we leave space for many truths.

Liked this story? Check out some of my other ones here: