Table of Contents

It’s early April, and something strange is happening in Iran. Schools are empty. Offices are abandoned. Once-busy streets are quiet. Parks, on the other hand, are overflowing with people.

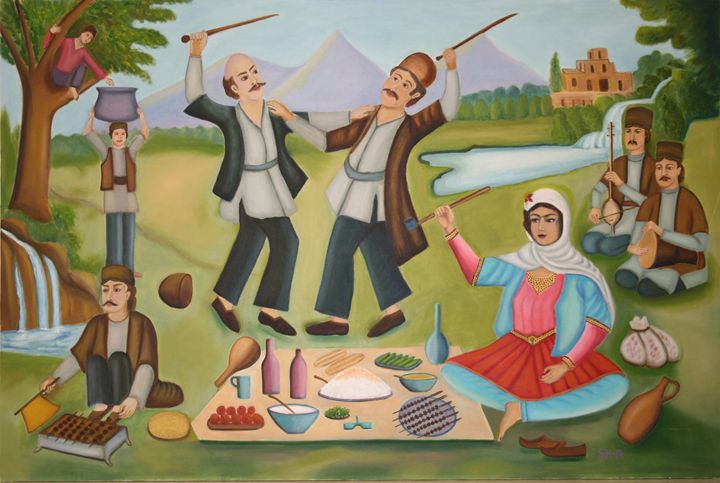

In Iran on the 13th and final day of the Persian New Year, absolutely everyone heads outside to parks, riversides, and mountains. It looks like the entire country has collectively decided to skip work and go on a picnic. Families spread out blankets, kids play games, and strangely, someone in every group is chucking handfuls of greenery into a stream.

This isn’t just a nice day out—it’s Sizdah Bedar, a national holiday dedicated to ditching bad luck and embracing nature.

Persian New Year

Persian New Year, or Nowruz, is celebrated by about 300 million people across central Asia every year. Nowruz has been celebrated for around 3,000 years, and has its roots in Zoroastrian mythology.

Above: Women from Jazira Canton in northeast Syria get all dolled up for Nowruz. Image by Hawar News. Taken from https://hawarnews.com/en/jazira-canton-comes-alive-with-nowruz-celebrations

A long time ago, the story goes, there lived an ancient king called Jamshid. During his reign, there was this insane winter so harsh that people worried that it would kill every living creature.

I’m not sure how cold ancient Iran could get, but I’m guessing the ancient Persians had never heard about those -30 degree days during winters in northern Maine, where I come from. (Jamshid, if you’re still around somewhere…help…)

Anyways, our boy Jamshid wanted to save his people, so he constructed a gem-studded throne and then enlisted some demons to help raise him high above the earth. There he sat on his shiny throne, shining like the sun and outsmarting the crazy winter. All the inhabitants of the earth gathered, scattered gems around him, and proclaimed that this day was the ‘new day’, or Nowruz.

From there, Nowruz evolved into a thirteen-day festival marked with rituals involving fire, water, traditional dances, gift exchanges, poetry recitations, and all kinds of groovy things. The last day, called Sizdah Bedar, or Nature Day, involves some fascinating and quirky customs.

Warding Off Bad Luck

Since Sizdah Bedar falls on the 13th day of the Persian new year, it’s considered unlucky due to widespread associations of the number 13 with bad luck.

Most cultures try to avoid unlucky numbers. In Iran, they take a different approach: They throw a party in nature instead.

Nature is of central importance in Zoroastrianism, an ancient Persian religion, so it’s only natural that Persians would wrap up their new year with a lively outdoor gathering. They also believe that the positive energy that is generated by celebrating in nature with loved ones can expel negative thoughts from their minds, thereby starting out the new year on a good foot and warding off bad luck.

On that note, Sizdah Bedar involves a range of practices specifically centered around expelling bad luck and calling in good luck, all while having a grand old time in nature.

One of these customs is the throwing of ‘sabzeh’, or sprouted wheat or lentils, into moving water. This act is a way to symbolically throw away any bad juju accumulated during the previous year, making way for a fresh start as the new year begins.

Above: Sabzeh! Image by Saadat Rent. Taken from https://www.saadatrent.com/english/article/sizdeh-bedae-iran

Another custom, practiced by young singles, involves tying a knot in the stems of the sabzeh and pausing to silently make a wish for love and/or marriage before tossing it into the moving water in hopes that tying the knot in the greens will help them tie the knot in real life.

There’s also a variation in which some people might untie the knot after tying it, as a sign of releasing or untying obstacles in their love lives. Similarly, some say that opening the knot is equivalent to opening the luck.

Since Sizdah Bedar is celebrated not only in Iran but across central Asia, many different region-specific traditions have emerged. In Kurdish areas, for instance, there’s a custom of throwing thirteen pebbles over one’s shoulder to ward off bad luck.

Above: Throwing the sabzeh into moving water. Image by Akhtar Ghasemi. Taken from https://worldone.travel/blog/sizdah-be-dar-iranian-festival.

Surprisingly, the thirteenth day of the new year was not always associated with bad luck. In the ancient Zoroastrian calendar, each day of the month was given a name according to one of the faces of God, often represented by natural elements.

The thirteenth day of the month was called “Tir Rooz”, and it was associated with the god of rain. In ancient Persia, rain was seen as a sign of God’s kindness and generosity.

Actually, Sizdah Bedar is an ancient tradition of celebrating the victory of the God of rain over the demon who brings drought. The association with bad luck only came later, as many cultures across the world came to consider the number thirteen unlucky.

Persian April Fool’s Day

Sizdah Bedar has also earned a reputation as the oldest version of April Fool’s Day in the world. ‘Lie of the Thirteenth’, as they call it, has been marked by pranks since about 536 BC.

Just like on April Fool’s Day, people might spread false news, issue fake engagement announcements, and employ ‘look behind you’ tricks (as in ‘watch out, there’s a big spider right behind you!’) Since this holiday is marked by spending time in nature around water sources, one popular prank is to pretend to stumble and fall in the water, then enjoy everyone’s reactions.

After a full day of nature, rituals, laughter, and pranks, Iranians and central Asians head home, officially wrapping up their nearly two-week-long New Year’s celebrations. The bad luck has been tossed away, wishes have been whispered into knotted greens, and one last joke has been played before getting back to everyday life.

While Sizdah Bedar might not be on your calendar, it’s a reminder that sometimes the best way to ward off misfortune is to grab your friends, head outside, and partake in a little joyful chaos.